future here now…

Much of the coming transformation will depend on the stories and narratives that are adopted and the culture that is carried forward. Metaphors matter. Having witnessed the rise of transformational technology on Wall Street, the Internet and Web in Silicon Valley and more recently machine learning through the lens of a startup listening to stories at scale leveraging AI, one thing is clear: The culture that surrounds these transformations is as important as the technology itself. We need future architects and archeologists who can prioritize and capture the human story - an operating system based on the wisdom of our ;ived experience as context - ancestral and cultural intelligence through storytelling to guide the use of our artificial intelligence.

The Future is Here

We shape our tools and then our tools shape us. New technology has always profoundly reshaped society, culture and our economy. The railroad, radio, TV, the Internet all completely changed the way we experience life, each in unique and subsequently more profound ways. I have observed many of these shifts directly, including the introduction of instantaneous wire transfers on Wall Street in the 80’s, the Web in the 90’s, social media and many others. The recent breakthroughs in AI are powerful and game changing in ways we do not yet understand - that much we know. But these technologies alter not just how we communicate, but who we are. Marshal McLuhan observed that new media technologies don't just extend our senses - they dismantle and reconfigure our sense of self, community, and reality itself. Much of the coming transformation will depend on the stories and narratives that are adopted and the culture that is carried forward. Metaphors matter.

Historical Context in Finance

Long before I gravitated toward impact I was a bond trader and finance executive on Wall Street. It was the early 80’s and I was enamored with the chaos and complexity of markets. My arrival coincided with the introduction of the SWIFT system for wiring money internationally. Before SWIFT the state of the art system for transferring money was Telex, a public system involving manual writing and reading of messages. Little did I know at the time just how much this technology would change the nature of banking itself. The speed and ease with which banks and financial institutions could now transact together moved much more quickly than anyone could imagine. The unintended consequences were profound.

Too big to fail originated with the collapse of Continental Bank signaling a new unspoken monetary policy.

After a short stint in investment banking at Continental Bank in Chicago working for Rose Friedman, the wife of infamous economist Milton Friedman, I moved to the Treasury Department where I learned how to manage the risk of the bank. In late April and early May 1984 I began to see men in dark suits show up for very long conversations in closed conference rooms. The regulators had arrived. Rumors began to spread. On May 10, 1984 the Bank’s president, Bob Taylor, walked into the Treasury Department. He was a distinguished, good looking man with a slow purposeful gait. Today he had a nervous smile, and his eyes sort of glazed back and forth across the room. That day, rumors of the bank’s insolvency sparked a massive run by its depositors. By that time Continental Illinois had purchased $1 billion in speculative energy-related loans from now bankrupt Penn Square Bank.

The FDIC estimated that nearly 2,300 banks had invested in Continental Illinois through loan participation agreements that tied their fate together. For the first time in history the words “too big to fail” were being uttered. To let Continental fall might just create a cascading failure of other big money center banks endangering the entire financial system, just as the collapse of Penn Square had caused the demise at Continental Illinois. This became the first time the term “too big to fail” was used to describe a new monetary policy reality.

Wall Street culture enveloped me back then. The thrill of my new found access to the “control room,” where the technology allowed me to move billions of dollars as “an insider” was intoxicating. And of course there was the money. The culture lured you in and the money kept you there.

The Rise and Cultural Shift of Big Tech

I left banking in 1994 for San Francisco. Just in time to witness the birth of the Web and the DotCom, the utopia and the bust. I watched the optimism and hope for a better world turn into the failed dreams of starry eyed entrepreneurs (myself included) as the bigger tech players picked up the pieces. Perhaps most importantly I witnessed the birth of “big tech culture.”

When VR pioneer Jaron Lanier addressed the New Mind’s audience at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in 1997 he spoke about the structural brilliance of the Internet’s underlying communication protocol TCP-IP enabling “any node to talk to any other node” as if it were as revolutionary as the US Constitution’s impact on democracy and freedom. “You are writing the new constitution” he said to the 700+ tech enthusiasts in San Francisco I had gathered to address the impact of tech on society and culture. His words couldn’t have been more profound. The medium as protocol moved us from centralization to decentralization of the world in one fell swoop.

Two powerful cultural narratives dominated the scene at the time - Burning Man and cyberpunk.

Two powerful cultural narratives dominated the scene at the time - Burning Man and cyberpunk. 2,000 people were attended Burning Man when I arrived in 94. When I left in 2003 there were 30,000. Burning Man had become a creative outlet for techies in the Valley - a place where you could prototype a gift economy around a communal fire. By day Burners built companies for others. By night they let their imagination run free as they designed and built outrageously interesting artifacts for the annual desert festival, an immersive art and technology playground.

Many in the Valley at that time were also inspired by cyber-punk authors like William Gibson and his book Neuromancer, as well as Neil Stephenson’s Snow Crash, the 1992 cyberpunk classic where the metaverse was first coined. The evolution of Burning Man and cyberpunk culture is foundational background for understanding how the big tech culture we know today came to be. While Burning Man was prototyping a new creative culture, cyberpunk heroes idolized masculine outlaw behavior, and as critic David Brin put it: “Orwellian accumulations of power in the next century, but nearly always clutched in the secretive hands of a wealthy or corporate elite.”

Today this wealthy elite is typified by the so called Magnificent Seven - a group of large-cap technology companies that have dominated the U.S. stock market in recent years. (Amazon, Apple, Alphabet, NVIDIA, Microsoft, Tesla and Meta).The combined weight of these companies in the S&P 500 has at times exceeded 35%, meaning the performance of just these seven stocks can significantly sway the entire index.

As Burning Man slowly became a playground for the elite, it became more and more obvious big tech culture had adopted a cyberpunk vision of the future. The moniker Magnificent Seven is actually from an old 1960’s Western of the same name, featured seven gunfighters hired to protect a village. According to Forbes, “In the stock market context, these seven companies are seen as protectors and drivers of market growth, especially during times of economic uncertainty.”

Each of the seven CEO’s of "The Mag 7” companies are male. Orwell has never been more relevant and AI is now clearly in the hands of a wealthy elite. How might that ever change? Where might a new more compassionate, transformative narrative and culture emerge that puts the needs of humanity first and technology in support? Where are the artists and storytellers now?

Toward a New Transformative Narrative

The great literature professor Joseph Cambell suggested any new mythologies worth thinking about, beyond religion and science, “would be centered around our planet Earth.” A bright spot on that front is the work of Tom Chi, founder of At One Ventures whose mission is to help humanity become a net positive nature. “At One” refers to being at one with ourselves, nature and the universe. They do this by investing in early stage deep tech for climate and environment, using venture to disrupt issues doing the most damage to nature. Air, water, soil and biodiversity. What would it mean to adopt a “net positive to nature” culture? How could we center this metaphor to lead the development of AI?

Physicists David Bohm and more recently Roger Penrose have articulated how reality at the quantum level is based on an indivisible wholeness. Despite our attempts to mechanize the theory to comport with classical physics it defies logical, linear ways of understanding the universe. "Consciousness must be beyond computable physics" says Nobel physicist Roger Penrose. Mind is not algorithmic. Understanding life and the universe as completely interconnected means that humans must be entangled together as much as photons are. Seeing life and reality this way will take some time but the sooner we do the better. Yet there is no time like the present to imagine and create a net positive to nature culture.

Kim Stanley Robinson’s Ministry of the Future, Octavia Butler’s Parable Series, Joana Macy’s The Great Turning all write about a kind of regenerative futurism that imagine compelling alternatives to despair and blind faith in tech.

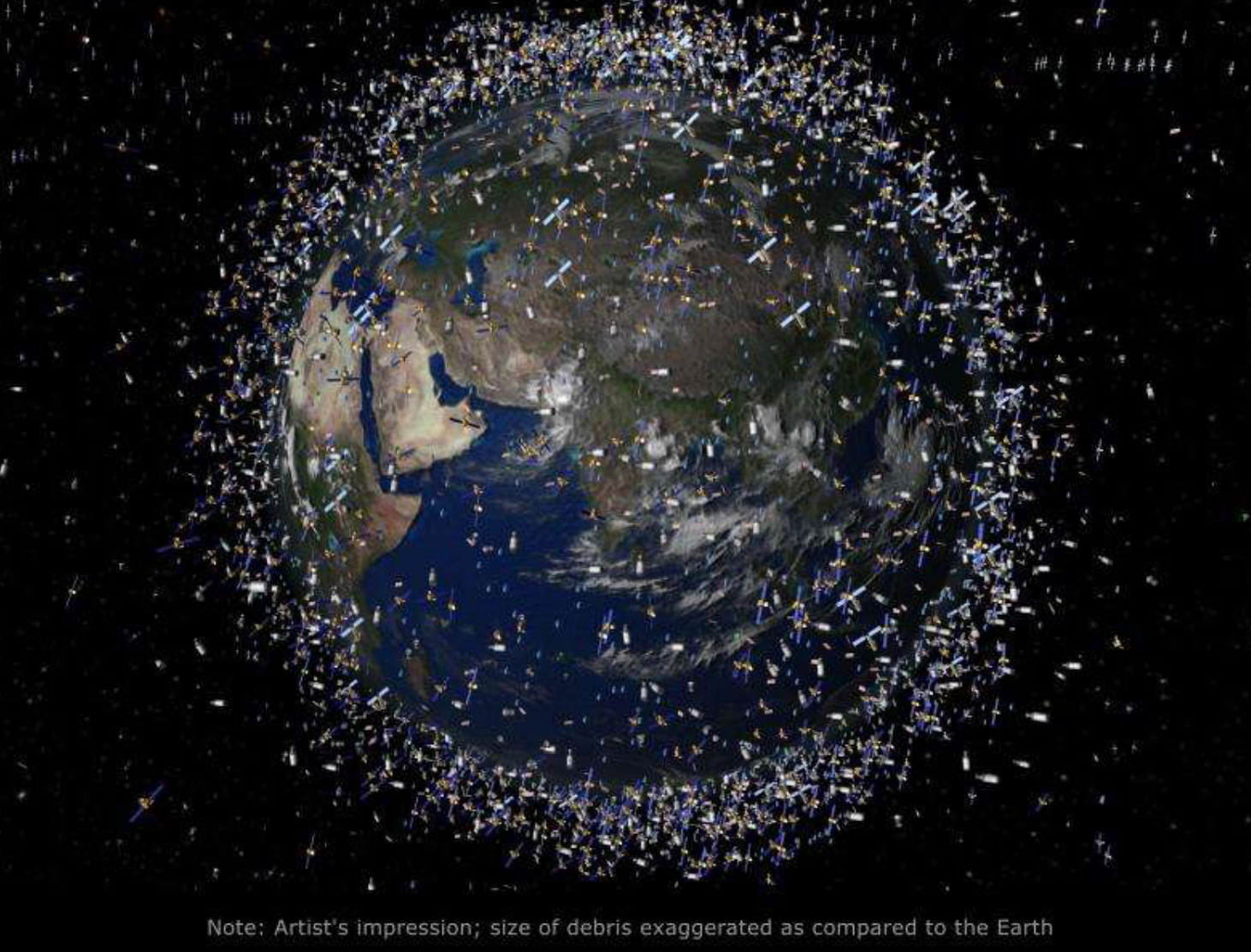

“The planet has grown an external layer of satellites, cities and various physical networks, all of which constitute a kind of sensory epidermis or exoskeleton... an artificial crust…” Antikythera

The creative think tank Antikythera articulates how humans and planet are inseparable from the tools we develop calling it “planetary computation:”

“The planet has grown an external layer of satellites, cities and various physical networks, all of which constitute a kind of sensory epidermis or exoskeleton... an artificial crust through which it has realized incipient forms of animal-machinic cognition with terraforming-scale agency.

Nevertheless this new skin is primitive. It is not yet a complex coordinated sensory system in the same way our own skin for example is able to send messages to the brain crucial for our survival and well-being. We need a new form of social-technological observatory to ground our abundance of data in service of our local communities - the places where we live, breathe, gather, celebrate and build.

This requires future architects and archeologists who can prioritize and capture the human story, without extraction for monetary gain, but as context, capturing ancestral and cultural intelligence through storytelling to guide our artificial intelligence. Amoofy is doing just that.

I am also inspired by a renewed comprehensive design movement surfacing in places like the Stanford Center for Design Research and the Buckminster Fuller Institute focusing on comprehensive thinking for collective action.

How do we move in this direction, where comprehensive, wholistic, imaginative thinking and spaces for deep reflection lead to cooperative action on the ground?

We can start by slowing down.

The current era requires a different type of attention. A way of seeing more like sonar. An acoustic, 360 degree awareness. In such an environment we can start by giving ourselves more empty space, more time for reflection to feel the rhythms around us.

And by imagining and building new mediums, technologies and businesses which by their very nature propel us to reestablish our individual integrity as whole persons, nurtured by interconnected living systems.

Sound like science fiction? So did the metaverse in the 1990's.

The future is here, it’s just not well distributed yet.