We live in extraordinary times. We live at a time when one global paradigm is giving way to a new one. The industrial atomic age is present but giving way to an information and knowledge based paradigm. We are now accustomed to the explosion of new technologies arising in every discipline while at the same time instant, always on communications and interactive media are making the world a much smaller place. Yet these tools have been mostly aimed at producing more goods and services, not directly aimed at improving our lives. We know its time to directly connect our ideas and technologies to a singular end - improving our well-being. But what kind of meta-infrastructure can support the development of real solutions to real needs, simpler lifestyles and local, community based relationships that benefit from global decision-making structures? What structure embraces the empowering nature of these new technologies?

After spending eleven years on Wall Street and another ten or so in technology I was led to social enterprise, also known as social capital or impact investing. Now that social capital is rising as a thriving, emerging market it is important to find the intersection with the new age described above. In fact, I think its high time for an intelligent and lively debate around the economics and ecology behind the social capital markets and how they relate to the existing capital market system now under siege. A rigorous framework to analyze the inherent contradictions arising from the two models is called for as we move toward a long term model of sustainability - suitable to the age ahead. Issues to be discussed include the dynamics of big corporations and what they can learn from small, nimble, transparent social enterprises; philosophies of scarcity versus abundance; the implications of openness and transparency on private property systems and clear definition around the kind of meta-institutional framework to be put in place.

I think its helpful to begin by looking closely at the work of Paul Romer and Joseph Stiglitz, arguably the most respected economists out there thinking about the economy beyond the old paradigms. Both address the potential for new institutional frameworks in the age ahead.

economy |iˈkänəmē|noun ( pl. -mies)1 the wealth and resources of a country or region, esp. in terms of theproduction and consumption of goods and services.• a particular system or stage of an economy : a free-market economy | the less-developed economies.2 careful management of available resources : even heat distribution and fuel economy.

ORIGIN late 15th cent. (in the sense [management of material resources] ): from French économie, or via Latin from Greekoikonomia ‘household management,’ based on oikos ‘house’ +nemein ‘manage.’ Current senses date from the 17th cent.

According to an

interview with Reason Magazine Romer's innovation, expressed in technical articles with titles such as "Increasing Returns and Long-Run Growth" and "Endogenous Technological Change," has been to find ways to describe rigorously and exactly how technological progress brings about economic growth.

In particular he articulates the need to distinguish but link basic research and market innovation and to re-examine the institutional forms most appropriate in encouraging the flow of new ideas - when for example they should flow through market systems and when they should flow freely unencumbered by patent and intellectual property laws. How do you incentivize research and experimentation to develop effective AIDs medications while sharing the public benefit of those breakthroughs with those most unable to afford them?

"If you're going to be giving things away for free, you're going to have to find some system to finance them, and that's where government support typically comes in," Romer says..."In the next century we're going to be moving back and forth, experimenting with where to draw the line between institutions of science and institutions of the market. People used to assign different types of problems to each institution. "Basic research" got government support; for "applied product development," we'd rely on the market. Over time, people have recognized that that's a pretty artificial distinction. What's becoming more clear is that it's actually the combined energies of those two sets of institutions, often working on the same problem, that lead to the best outcomes."

Stiglitz, the Nobel Prize winning ex World Bank Director also known for his public and derisive view of the International Monetary Fund, laid the foundations for the theory of markets with asymmetric information (i.e. markets are not so efficient) which lead to his conclusion there is no "invisible hand."

"The theories that I (and others) helped develop explained why unfettered markets often not only do not lead to social justice, but do not even produce efficient outcomes. Interestingly, there has been no intellectual challenge to the refutation of Adam Smith’s invisible hand: individuals and firms, in the pursuit of their self-interest, are not necessarily, or in general, led as if by an invisible hand, to economic efficiency". (More here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Stiglitz )

This was finally acknowledged by former head of the Federal Reserve Alan Greenspan in his testimony before Congress - an amazing admission by the former chairman. See http://www.linktv.org/socap08

Stiglitz new book Stability with Growth: Macroeconomics, Liberalization and Development offers a variety of non-standard ways to stabilize the economy and promote growth, and accepts that market imperfections necessitate government interventions.

But looking at things purely in economic terms leaves me wanting more. Certainly we can’t just rely on a more interventionist government to prevent or redress market failures? On the other end of the spectrum is

Douglas Rushkoff who as an independent thinker and writer, articulates the incongruity between the technologies that drive our economy today and the financial structures currently in place. Rushkoff’s background is in media, technology and culture but he is well versed in economic history. His controversial but provocative new book: "Life Inc... how the world turned into a corporation and how to turn it back" is set to arrive soon... for a preview I highly recommend

listening to him speak about these issues.

Rushkoff suggests we approach the new age not just from an economic perspective but from an ecological perspective, one that takes into account the interaction of people with their environment. The speculative economy doesnt just need a fix. It needs to be replaced by a "real economy."

ecology |iˈkäləjē|noun1 the branch of biology that deals with the relations of organisms to one another and to their physical surroundings.• (also human ecology) the study of the interaction of people with their environment.

ORIGIN late 19th cent. (originally as oecology): from Greek oikos ‘house’+ -logy .

According to Rushkoff "The real economy need not suffer in the downfall of the speculative economy. If anything, the real economy has been repressed by the speculative economy. Real farmers have been crushed by Big Agra, real druggists have been crushed by Wal-Mart and real transportation alternatives have been crushed by Big Oil and Big Auto.

The opportunity here, while the big boys are down, is to rebuild the genuine, local commercial infrastructure. To make shoes, clothes, food, education, healthcare and everything else we can in a bottom-up fashion. While speculators enjoy the economy of scale, we inhabit an ecology scaled to the human being that was lost in the corporatist equation."

The economic structures now in place were developed for an older industrial model based on scarcity, the extraction of value from planet and people, a disconnect between management and the stakeholders served, and an underlying value system centered on self-interest. At the heart of this was the corporate structure.

Corporations and the economic system behind it are based on debt instruments marketed as brands to identify with consumers isolated from their communities who rely on mass media and mass markets instead. Money is not earned into existence it is lent into existence, Rushkoff notes, creating an insatiable need to work harder and longer to feed the hand that lends.

Rushkoff argues that the decentralizing technologies fueling the digital age put the power of creation back in the hands of the individual and the community in direct opposition to the very nature of a centralized corporate structure. The digital age allows individuals to be creators of ideas and knowledge, to compare notes and collaborate with communities near and far, to create social capital and currency that may be exchanged for real needs.

But just how exactly do you create enterprises from the bottom up that are locally responsive and responsible and financially sustainable, while at the same time able to take advantage of scale where appropriate, but not forcing it? This is precisely where social enterprises figure greatly into the overall equation. Social entrepreneurs have been experimenting with just such approaches and with greater and greater success. Stonyfield Farms, Body Shop, Calvert Funds, Smith & Hawken, Honest Tea, and Ethos Water are some of the more well-known social enterprises but a very deep pool of these kinds of enterprises can be found around the world in industries like microfinance, fair trade and renewable energy.

Social entrepreneurs and the investors behind them have also been great innovators in the kind of institutional issues Romer suggests are crucial - that is finding a spectrum of approaches on where to draw the line between research and development and market based efficiency, between for-profit and non-profit structures and between local and global strategies.

What we are talking about here is harnessing our countries culture of entrepreneurship and innovation but now directed toward social and environmental ends, or "social innovation." In combination with technological innovation we have the basis for building a real economy at local and global levels that can replace the speculative economy. But it will require us to rebalance our incentive structures through public private partnerships that supports risk taking entrepreneurs set on improving our lives and communities. It will require smart regulation that reinforces new behavior. And it will require new corporate models that makes explicit the bargain of a balanced set of returns - social, environmental and financial. There is real, practical knowledge arising from social enterprise that can be transferred directly at the governmental level potentially through the new Office of Social Innovation, and through the corporate ranks through "social intrapraneurship "- (social entrepreneurs working within large organizations). All of the above needs to be translated into concrete terms and structures.

But let us also take this opportunity to be clear about why we are doing this. Its not because the financial system has collapsed. That is a symptom of our singular focus on economic self interest - increasing individual income levels through more and more consumption. I would suggest our rediscovered purpose in the new age means increasing individual and collective well-being by sharing new ideas and technologies sustainably.

Well being - An understanding or valuation of “human” that takes the whole human being as the basis of valuation not just economic well being.

In my work with Halloran Philanthropies and Hardin Tibbs on well-being we have asked ourselves "How have human needs been met in the past." The industrial-era answer to this question is “by expropriation” – we take what we need from nature and from other human beings. This answer sees the human being as having mastery over nature and as being able through technology to be independent of environment and society. A wiser answer is that we depend on our environment and on other humans. Thus the need to think about ecology - the relation of organisms (people) to one and other and to their environment. Social entrepreneurs are demonstrating how to do this every day.

A shift from focusing on income to well being does not mean accepting less. On the contrary, it means doing more with less through better design and technology. A new paradigm that acknowledges this as our shared American Dream is what will really change the world.

mark

After 2 years of spreading the message on the ground in Washington DC finally a breakthrough. The SBA announces the creation of a $1 billion "Impact Investing Fund." Although not equity and although the details have not yet been released, it is a strong indication that the different parts of the Obama administration are starting to incorporate the work we and others are doing to support the development of the "impact investing" marketplace. Here is a link to the Enterprise Innovation Fund proposal we have been promoting and here's a link to an article written on this development and others from an interview I did.

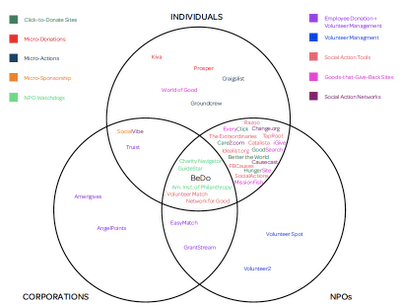

After 2 years of spreading the message on the ground in Washington DC finally a breakthrough. The SBA announces the creation of a $1 billion "Impact Investing Fund." Although not equity and although the details have not yet been released, it is a strong indication that the different parts of the Obama administration are starting to incorporate the work we and others are doing to support the development of the "impact investing" marketplace. Here is a link to the Enterprise Innovation Fund proposal we have been promoting and here's a link to an article written on this development and others from an interview I did. I believe the sustainable social media and stakeholder engagement field is beginning to take off providing great investment opportunities over the next few years. This covers a range of niche markets ranging from micro-investment sites like Kiva, Microplace and Social Vibe to to corporate CSR, employee engagement and volunteer sites like Angel Points and Network for Good. (See landscape map below).

I believe the sustainable social media and stakeholder engagement field is beginning to take off providing great investment opportunities over the next few years. This covers a range of niche markets ranging from micro-investment sites like Kiva, Microplace and Social Vibe to to corporate CSR, employee engagement and volunteer sites like Angel Points and Network for Good. (See landscape map below).

The formation of tribes dates back over 3 million years. I think their modern equivalent may be one of the key structural missing pieces that link intention and behavior across our most basic modern organisms - individuals, families, corporations and NGO's - to generate human and ecosystem well-being.

The formation of tribes dates back over 3 million years. I think their modern equivalent may be one of the key structural missing pieces that link intention and behavior across our most basic modern organisms - individuals, families, corporations and NGO's - to generate human and ecosystem well-being. Compare this to Buckminster Fuller's thinking on the great migration of peoples across the Bering Strait and throughout the world which, he said, has resulted in millions of years of disperse, isolated experiments in how to survive, how to process information and how to get along. Because these experiments were isolated, they were preserved in diverse cultures around the globe. The construction of our advanced transportation and communication systems, he thought, were now acting to integrate this disperse knowledge.

Compare this to Buckminster Fuller's thinking on the great migration of peoples across the Bering Strait and throughout the world which, he said, has resulted in millions of years of disperse, isolated experiments in how to survive, how to process information and how to get along. Because these experiments were isolated, they were preserved in diverse cultures around the globe. The construction of our advanced transportation and communication systems, he thought, were now acting to integrate this disperse knowledge. A Hopi Elder Speaks:

A Hopi Elder Speaks:

On January 14 Wayne Silby, Founder of Calvert Funds, and I attended a meeting of the Obama Transition Team in Washington DC after being asked to present a proposal for a new Enterprise Impact Investment Vehicle that would create a public - private partnership between private investment managers and the Government to generate more capital investment into social enterprises.

On January 14 Wayne Silby, Founder of Calvert Funds, and I attended a meeting of the Obama Transition Team in Washington DC after being asked to present a proposal for a new Enterprise Impact Investment Vehicle that would create a public - private partnership between private investment managers and the Government to generate more capital investment into social enterprises.